It is very likely that you have already interacted with one of these systems. Perhaps you asked ChatGPT for the most efficient route to explore Madrid, or noticed how your email application now completes your sentences coherently. Large Language Models (LLMs) have undoubtedly brought about a profound change in the way people interact with technology, an innovation that, until recently, seemed to belong to the realm of science fiction.

This emerging technology has initiated a new, cross-sector industrial revolution. Beyond the boundaries of factories and office environments, its applications have reached the everyday lives of millions, demonstrating an almost boundless potential for transformation.

The following section explores the underlying principles and technological developments that have made this unprecedented evolution possible.

How Does a Computer Understand a Word?

This was one of the main challenges in the field known as Natural Language Processing (NLP). Translating human language into formal rules that a machine can interpret is an especially complex task.

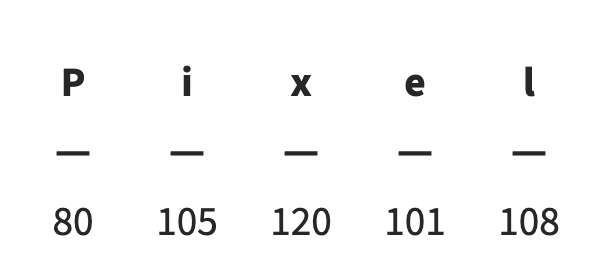

Over the past few years, several approaches within the broader domain of Artificial Intelligence, such as Neural Networks, have been refined to process a wide variety of data. However, these methods require information to be digitized before it can be analyzed. So, how can a word like “Pixel” be represented numerically? One of the most intuitive ideas might be to treat the word as a set of characters. By assigning a numerical value to each letter, the entire word can then be expressed as a vector of numbers (as shown in Fig. 1).

Fig 1. ASCII code representation of each character in the word “pixel.”

Another possible approach is to use a human–machine dictionary containing all existing words arranged alphabetically, with each assigned a unique identification number. Finally, one of the methods used by GPT models involves dividing each word into subwords, creating a sequence of smaller units that together form the complete word.

Each of these methods represents a word in a different way, using units known in this field as tokens. Every token is not only assigned a number, but also a numerical vector that allows it to be uniquely identified. But what criterion is used to assign these numerical values to each word?

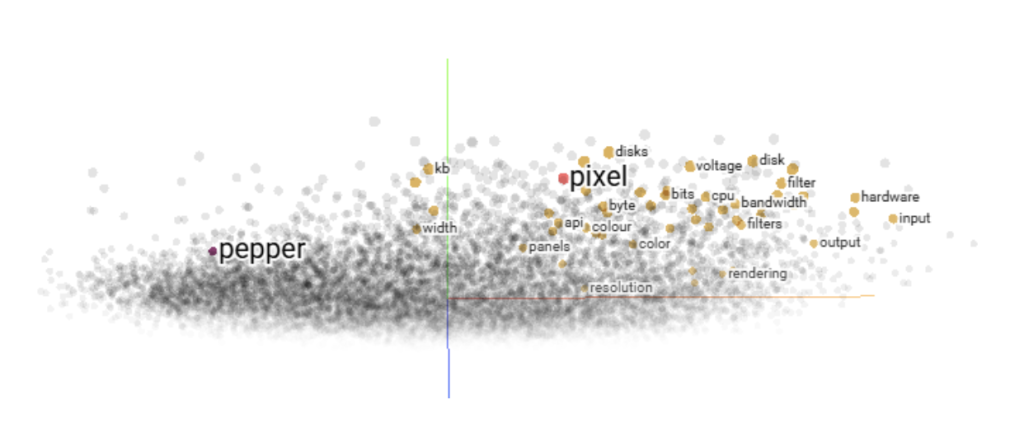

One of the most intuitive approaches is to ensure that words with similar meanings, such as “Pixel” and “Image”, are placed closer together in the vector space than unrelated words, such as “Diabetes.” The mechanism that enables this step is known as embeddings.

One of the most widely used systems for generating these embeddings since its release by Google is Word2Vec. There are visualization tools that project these relationships into a 2D or 3D space, allowing us to see semantic similarities between words. As shown in Figure 2, “Pixel” appears much closer to “Byte” or “Color” than to “Pepper.”

Fig 2. Graphical representation of words processed by Word2Vec after applying PCA.

From Words to Sentences: The Challenge of Memory

Now that we can convert words into data, the next question arises: how can we make machines interpret full sentences? To address this, researchers proposed the use of Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs), which can process words sequentially to form a sentence. This allows each word to be understood not in isolation, but in the context of the words that come before it, providing meaning to the overall phrase.

This approach works reasonably well for short sentences but faces a fundamental limitation in memory. Imagine trying to recall the very first word you spoke today. These networks face a similar issue: it becomes increasingly difficult for them to retain the same level of importance for earlier words as new ones are processed over time.

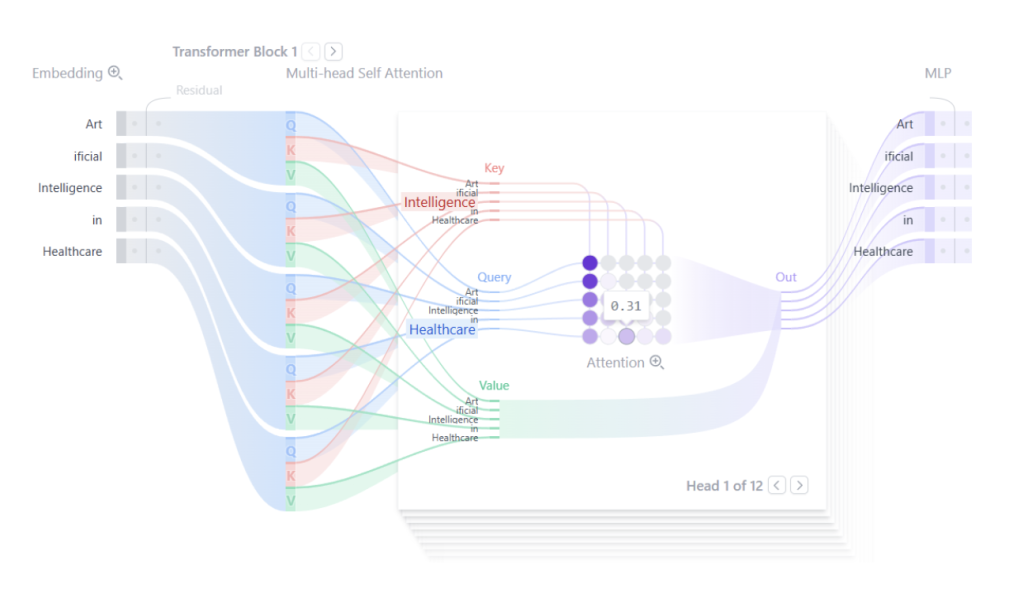

In 2017, an ingenious solution emerged that would not be forgotten: the Transformer. This neural network architecture introduced a mechanism known as attention. Through this system, greater weight is given to the words or concepts most relevant to understanding a sentence and their relationships with one another.

This innovation largely overcame the memory problem, as the distance between words was no longer a barrier. The model could simply focus attention on the most meaningful parts of the sentence. If we visualize what happens inside a Transformer, it would look something like Figure 3, where in the sentence “Artificial Intelligence in Healthcare” a strong relationship can be observed between “Intelligence” and “Healthcare”, indicating their semantic connection.

Fig 3. Graphical representation of the transformer process.

Using Wikipedia to Train Predictive Language Models

So far, we have seen how a sentence can be converted into something a computer can read, but what about understanding it? One might assume that a machine would need an extensive set of grammatical and formal rules to comprehend a sentence. However, this would require a large number of people manually labeling the data, indicating which word is the subject, which is the action, and so on.

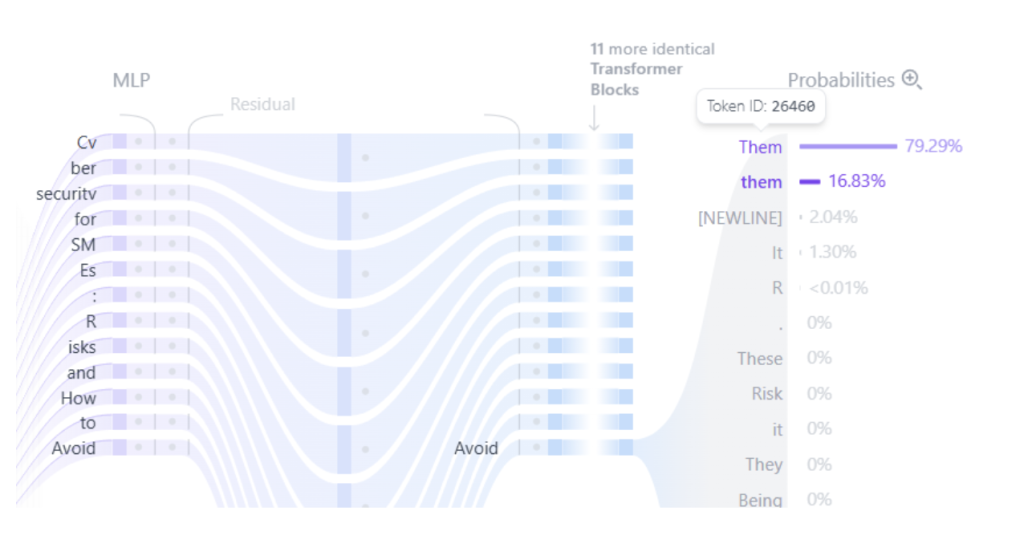

The actual solution turned out to be much simpler. The key task for which language models are trained is autocompletion. Consider a sentence such as “Transforming waste management with AI.” Now remove one of the words. Could you guess which one is missing without reading it? This is the fundamental idea behind training these systems.

By repeating this process millions of times using massive amounts of text freely available on the Internet such as Wikipedia, books, articles, or conversations, highly complex and accurate models can be trained. Similarly, if the model learns to predict the last word of a sentence each time, it can generate entire phrases in response to a user’s prompt.For instance, Figure 4 shows a prediction example for the sentence “Cybersecurity for SMEs: Risks and How to Avoid ___.” The model correctly identifies “Them” as the most likely missing word among the available options.

Fig 4. Result of a transformer prediction.

The Present and Future of Human–AI Coexistence: The Cognitive Copilot Era

Generative text-based AI has moved beyond the laboratory to become a tool accessible to everyone. The deepest impact of this technology does not lie in its ability to replace human tasks, but rather in its capacity to augment our abilities. We are entering the era of the cognitive copilot.

For a programmer, it is an assistant that helps debug code. For a scientist, an expert that summarizes complex research. For an artist, a source of inspiration that helps overcome creative blocks. This democratization of capability is the true revolution: the power of a data center placed at the service of an individual’s curiosity, amplifying the workshop of ideas within each of our minds.

However, this powerful copilot is not free from turbulence. We must remain aware of its limitations in order to navigate safely. The first is bias: these models learn from the digital reflection of humanity stored on the Internet, and that reflection includes our prejudices. An LLM can therefore perpetuate stereotypes if it is not properly guided and corrected. The second is veracity: a model does not know whether something is true; it only knows whether it is statistically probable. This can lead to the generation of “hallucinations”, answers that sound convincing but are in fact false.

This reality compels us to redefine our own skills. The future does not belong to those who memorize facts, but to those who can ask the right questions, apply critical judgment to AI-generated answers, and learn to collaborate creatively with these systems.

Perhaps the best way to illustrate this new symbiosis is through an act of transparency: in fact, most of the section you’ve just read was written by an LLM.

Referencias

- Vaswani, A., Shazeer, N., Parmar, N., et al. (2017). Attention Is All You Need.

- Mikolov, T., Chen, K., Corrado, G., & Dean, J. (2013). Efficient Estimation of Word Representations in Vector Space.

- Radford, A., Narasimhan, K., Salimans, T., & Sutskever, I. (2018). Improving Language Understanding by Generative Pre-Training.

- Hochreiter, S., & Schmidhuber, J. (1997). Long Short-Term Memory.

- Alammar, J. (2018). The Illustrated Transformer.

- Christopher Olah. “Understanding LSTM Networks”.

- Karpathy, A. (2015). The Unreasonable Effectiveness of Recurrent Neural Networks.